(So I think I will be constantly updating this particular post every time I add a new musician so be sure to check back occasionally)

Jazz music was once considered indescribable. How do you put a definition on

something like this? Who would be so soulless as to try and tack on a hard

meaning to a movement based around ingenuity, based around spontaneity. Jazz

was meant to be an art form that was as a fluid and yet able to nail not only

the emotions of sadness or delight but every step that a person could take in

between; sometimes all within the same song. After a while people realized that

the words we used to say that jazz could not be defined did just that. It wasn’t

like a mystery was revealed but the movement just kind of congealed to the

general public.

Regardless the question still remains, especially for our

generation, how does one “listen” to jazz music? Among my friends here I often

hear jazz described as “classy” music or that listening to jazz makes them feel

like too fancy. Perhaps it is due to the inherent old world association they

have with jazz or due to the various jazz collections in their parents CD and

record library. To me this is a

very sad pretense for people to carry. All in all it limits people’s

perspective on jazz and causes them to inherently write it off as novelty. It

is my personal opinion that jazz is a unique musical art form not due to it’s

culture of inventiveness or it’s embodiment of freeform artistic creation. Jazz

is a unique as an artistic vehicle for transposing an individual’s emotions and

personality into song.

So with that in mind I shall begin the delving into jazz

music, particularly that of late 50s and 60s era jazz. I shall break down for

you some of the greats of the field and fill you in on a little bit of their

personal life and how that comes through in their music. Like I said, every

jazz musician is unique in and of himself. They may be using the same

instruments but the great jazz players are able to force their own style and

personality to the point where no two jazz players are alike. Of course, I want

you to keep an ear out for the things I mention about each musician but also I

would like to hear your personal take on their music as well. Often times it

seems no two people hear jazz the same way.

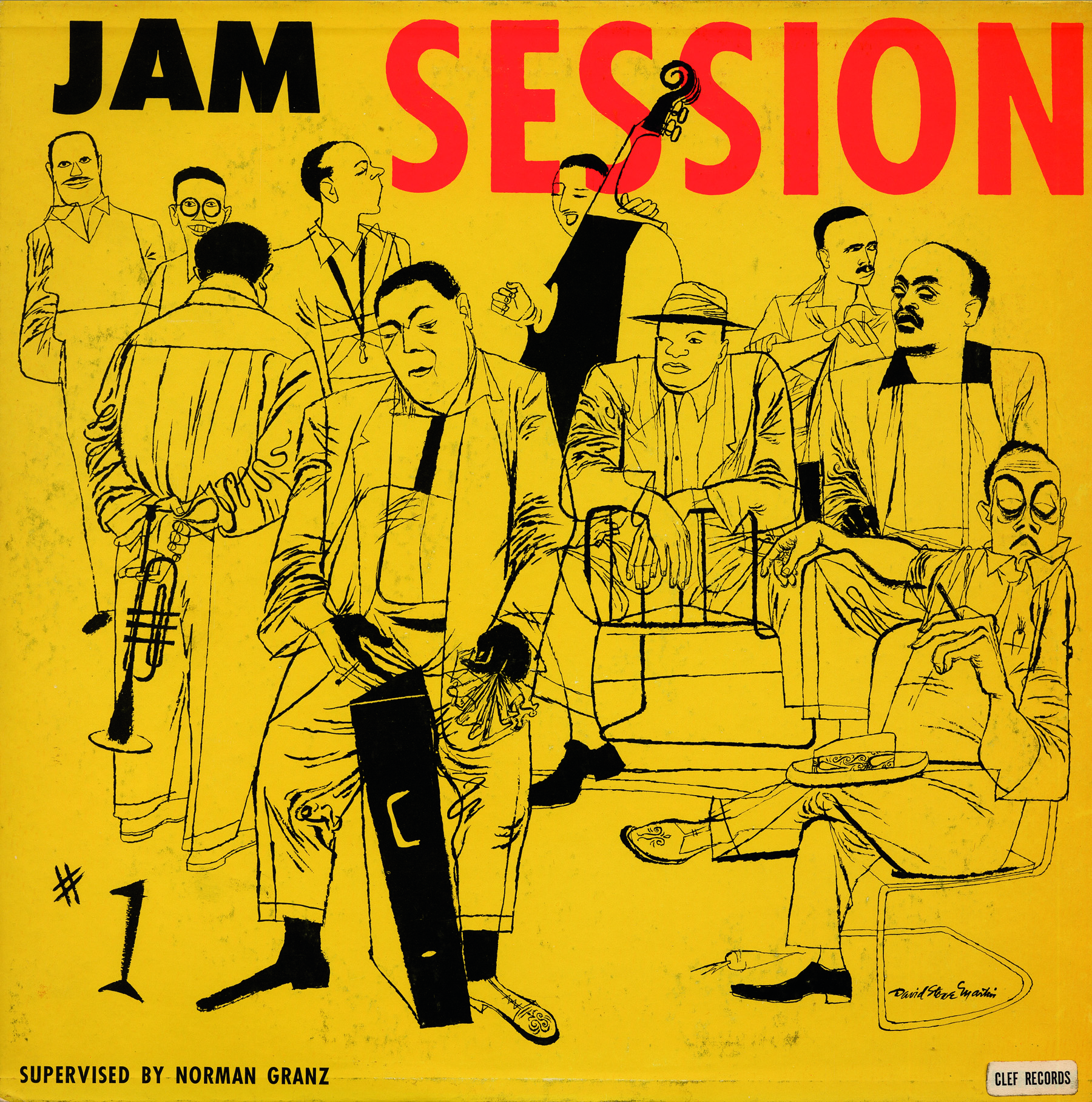

Without further ado lets dive in to Jazz starting with the

crown prince himself….

Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington may be the perfect jazz musician. In any event he is often regarded as the best. He is something of a granddaddy of that 50s 60s jazz era that I hold so dear to my heart. If you had talent in the jazz world, eventually, inevitably you were going to be compared to Duke. Of course that was a comparison of the highest honor. In all of Duke's songs, true to his character, there never seemed to be a hair out of place. Both on stage and off Duke was regarded as kind with an air of control that flowed naturally from him. Of what little I know about Duke's personal life, compared to his peers in the field, he is squeaky clean. In a career path associated with drug abuse, sleepless night after night, self doubt and constant pressure in social life, society and the professional world Duke fared remarkably well. He lived to the age of 75 (fucking forever compared to some of his contemporaries) and from what I know he had no prevailing issue with drugs or alcohol (fucking impossible compared to some of his contemporaries) The guy even married his high school flame at the age of 19. For all of these reasons Duke was a hit both among jazz musicians and the general public at large. When looking at his track record, his instrumental talent and most of all the compositions he wrote it is no wonder that Duke is often considered one of the greatest American musicians, jazz or otherwise.

Duke was probably the first jazz musician I ever heard. My dad would often blast

Black and Tan Fantasy on Sunday mornings as he did chores or cooked breakfast. Chronologically, this song carries a vibe closer to the 40s era jazz with the grainy sound quality, the moaning and croaking instruments and the slow and loping pace. Duke's music would soon take on a more contemporary sound as the times changed but Black and Tan is a great opening sojourn into jazz music. Even with its fairly limited options it paints a vivid landscape both to your ear and in your mind.

Day Dream and

Prelude to a Kiss are probably two of my favorite Duke Ellington songs. I am a sucker for jazz ballads and down tempo and Duke just slays it with these two. Of course, as I have said before, Duke slays it in anything he puts his mind to. Perhaps the reason these two songs are so dear to me is because Duke manages to squeeze the very essence of the ballad out of these. They are soft without being pathetic and just varied enough that it doesn't feel like just going around in a mopey circle. Prelude perhaps as a little more depth and versatility than Day Dream but I turn to mush every time that piano intro to Day Dream comes on, or when that quivering trumpet begins its lonely march.

I know I have praised Duke's abilities as a composer and I feel like I should back it up. As we begin to trek through these musicians you are going to see Duke's songs pop up a lot. Every now and then a musician is going to want to have a ball and see how they fare toe to toe with the Duke. For one reason or another the song that I see emulated more than any other is

Take the A Train. For some reason this song is just a prime target for recreation. That opening is immediately recognizable, the beat of the song is flexible and can be manipulated without losing the final product and the composition is perfectly balanced. No one instrument or section seems to overpower the other. From the very beginning, Ellington nails that mood of those fast paced commutes through the underground of New York (ones we are all too familiar with by now) and from then on he lets the song breathe until each section of his orchestra has had its share.

If I have one qualm with Duke then it is that he is "too perfect" It may seem like a cliche but a lot of the greatest jazz musicians were egged on by their short comings. It was their quirks and the eccentricities that powered their music and Duke really seems to be free of that. In that one regard I would say I tire quickly of Duke. All of the compositional talent in the world can't save you from being a little on the dull side. It is rare that I will listen to an Ellington record all the way through these days. I usually just pick out one or two songs that meet my fancy and then move along. In future musicians you will hear what difference strife and internal conflict can make in a song. Especially when musicians cover Duke. Perhaps this is what keeps him at his granddaddy status. Duke is very much rooted in the 40s era of jazz and simply did not face the same issues of the rising 50s and 60s musicians. His music is the pristine stepping stone that other greats began to base their career off of. Maybe it would be nice if Duke had and edge but someone has to be the Jazz Constant. Without Duke we might not know what a clean and unaddled composition would sound like.

For better or worse, that's Duke.

Ben Webster

Remember how I said Duke's music was pristine jazz in that it didn't have any distinctive aspects be they good or bad? Well I would say that the distinctive aspect of Webster's music is love. Ben is affectionately referred to as "The Brute" in jazz culture. One listen to one of Webster's ballads and you will quickly realize just how much of a joke that nickname is. Ben is a big man and apparently he wasn't a stranger to a fight or two in his time but on the tenor sax he is as gentle as they come. Every note Webster squeezes out on that thing is practically dripping with love. He isn't timid, Ben can hold one hell of a solo and keep everyone captivated, but his music isn't grandiose like he is. It commands a room without shouting and somehow remains intimate the entire time as if he was playing for a specific loved one. Ben's pace too seems loving. He ambles his way through his songs, you can feel his weight as he strolls from one note to the next. He takes his time but the songs don't suffer from it. The listener instead is allowed to sit upon each individual note and absorb all of that emotion and weight for themselves.

Ben spent a large amount of his later life traveling abroad in Europe (and he would later die there) He was known to enjoy just playing his instrument on the street for the hell of it. For the joy of some random passerby that wanted a listen. In these ways Ben's personality was just as loving and affectionate as his music itself.